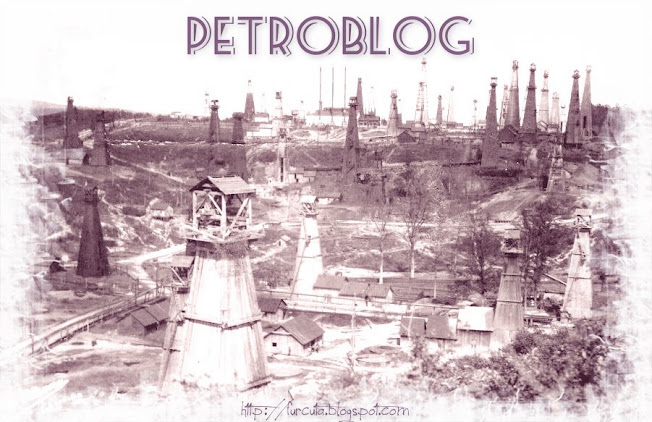

“Hundreds

of gigantic oil derricks, black toothpicks, 20 feet square at the base and as

hight as a 10-story apartment house. To the back of them mighty mountains, the

Carpathians, cutting the sky. In front the vast grain-laden plains throught

which the Danube is flowing to the Black Sea. Underneath hills of black sand tossed up in

all sorts of shapes, with black oil oozing from them and black streams and

pools of oil here and there. Huge, flat, round iron tanks 50 feet high in

groups each holding tens of thousands of barrels of petroleum. Iron pipe of all sizez lying on the ground,

stacked in piles, and being carried by long teams of white bullocks to this

place and that. Donkey engines pumping and bailing and a

myriad of dirty men and women toiling away at all sorts of strange jobs. These are some of the features of the oil fields

of Romania which lie here within gunshot of Ploiesti in southeastern Europe,

not far from the Balkans.

Oil

of Romania

The oil of Romania cuts a large figure in the

markets of the world. This country ranks sixth among the great oil producers.

She is now taking out almost two barrels of every hundread which are mined

throughout the world, and the bulk of her product comes from this little region

where I now am.

The Romanians oil deposits lie in three

zones. One is in Maramures along the Tisa river valley. Another is in the county

of Valcea, but the most important is that of Prahova, lying within two hours by

motor of the capital, Bucuresti, and on the southern foothills of the

Carpathian mountains. Here in a district, 10 miles wide and running for 100

miles along the slope of the hills are something like 1,000 oil wells, which

are producing from 7,000,000 to 9,000,000 barrels of oil per year.

The oil lies in great pools scattered here

and there throughout this 100 miles. They are in fields about 10 in number, and

the most important of all is the Moreni-Tuicani field which I describe in this

letter. It is a small territory. Put it all together and it would not cover

more then four 100-acre farms. Nevertheless, it yields more then half the Romanian

oil activity today. Not far away is the district of Baicoi, which I also have

gone over and in addition are eight or nine other fields, all of which contain

pools of petroleum.

Ploiesti

and its refineries

Ploiesti is a city of 70,000 in the center of

the oil producing territory. The fields run in a great semi-circle around it,

covering an area of perhaps 40 square miles, and the oil is piped here to be

refined. There are a dozen or more different refineries, the largest of which

has a capacity of 20,000 barrels a day. You can see the tank farms on every

side of the city, and the rich smell of petroleum fills the air.

The refineries belong to the great oil

companies which are working the territory. These are know largely by the

nations to which they belong. The Steaua-Romana is the German company; the

Royal-Dutch, is the Dutch-English, commonly known as the Royal Dutch Shell, and

the Romano-Americana is the Standard Oil company of the United States. In

addition there are a dozen or smaller establishments, for more then 100

companies are operating in the territory.

The Standard Oil refineries are the best in

the country. The machinery is all new, for it was built since the World war and

there is no modern process of oil reduction and production which it does not

possess. It is now refining something like 10,000 barrels daily, and it has

very large holdings in several fields. It was in company with Mr. J. P. Hughes,

the director of Standard Oil company here in Romania, that I went over the

fields, and to him and Mr. E. J. Dailey, the manager of the Moreni field, and

Mr. Fredericks, the manager of the Baicoi, and other of the Standard Oil men

employed here, that I am indebted for much of the information given in this

letter.

Great

Pools of oil

In

the first place, the oil formations are different from those of the United

States. In America the oil lies largely in a hard rock strata and the crude petroleum

flows or is pumped to the surface. Here the oil lies in great pools from 1,000

to 3,000 feet below the surface and is mixed with sand as fine as flour and

with the natural gas which permeates the whole. When oil is struck the gas

forces the sand out with the oil. Sometimes nothing but sand will come for

several hours and even days and then the mixture of oil and sand bursts forth.

Even after the wells have been producing for a long time, there is so much sand

mixed with oil that it is impossible to pump it. For this reason when the wells

stop flowing the oil is taken out by dropping a long bailing bucket, such as is

used in the making of any artesian well, allowing it to fill with oil, which is

held in by a valve in the bottom, and then raising it by machinery to the

surface and emptying the mixture of oil and sand. These bailers are driven by

machinery or steam and the bucket, which is as big around as a quart measure

and sometimes as high as a five-story building, is raised and lowered, carrying

up a number of barrels each time. With a bailer 50 feet long as many as 500

barrels of oil are thus raised in one day. Some of the bailers I saw carried

two and a half barrels at one load.

Getting the oil out of the sand is a large

parte of the production of crude petroleum in Romania. Every bit of the oil

comes up loaded, and in a flowing well it poures forth in a mush as thick as

molasses, as black as ink and loaded with these fine rock particles. The

particles are heavy, however, and they rapidly sink. The flowing well runs out

into a great vat half the size of a city lot and below this is a succession of

a half-dozen other vats descending in terraces. The oil flows into the first

vat and much of the sand is deposited as it passes into the second vat through

holes an inch or so in diameter. There more sand is dropped and the oil grows

purer and purer as it flows on through vat after vat until at the bottom it has

no sand at all and can be pumped by an engine through pipes into the great

storage tanks.

As the black, sand-loaded pitch flows from

the well it deposits much sand around the edges. This is scooped up by

bare-legged, bare-footed women, who stand ankle deep and often half deep, in

the hot, slimy mixture and ladle the mush out with scoops into holes or little

pits on the banks of the pool. Other girls lift the mush from these pools just

above, the oil draining out as they do and finnaly at the top, perhaps 10 or 15

feet above the great pool below, they raise the now almost clean sand and empty

it into a steel car in which it is carried away over a track to the sand pile.

In this field there were hundreds of

derricks, each over an oil well, and were mountains of sand here and there and everywhere among them, all

of which had been lifted out in this way. I asked as to the wages of these

girls and was told that they got 15 cents for a day of eight hours, or less

then two cents an hour for this back-breacking,

filth-scooping labor under the hot semi-tropical sun.

I took some pictures of the women at work.

They were almost in rags and some of them modestly arranged their short skirts as

camera snapped. A large part of the labor in the oil fields is done by women,

and here, as throughout the farming district, there are far more women workers

than men.

The wages of the men are more then those of

the women. Drillers get as much as 75 cents a day, but the common laborer

seldom recives more than 20 or 30 cents. The labor is not nearly so efficient

as that of the United States. The cost of living is very low and the people

think they do well.

Shooting

Grindstones

The sand mixed with oil entails difficulties

in drilling which we do not have in the United States.

The sand is as sharps as that of a

carborundum grindstone. It cuts like diamond dust and when a gusher is struck

it comes out with such force that the mush-like mixture will saw its way

through iron and steel. It will spray itself over a large part of the

surrounding country, and it is for this reson that the derricks are not left

open as in the United States, but boarded in from top to the bottom. In order

to break the force of the geyser of oil and sand a sheet of steel rails such as

are used for railways is hung about 20 feet above the mouth of the well. Every

other rail is inverted and the whole makes a solid block of steel.

Sometimes

a cap of iron, weighing three tons, or as much as three horse can haul, is

poised above the well and the sand cuts its way throught it as though with a

saw, the well shooting grindstones as it were.

The other day there was a man on top of a

derrick when one of these wells burst loose. He was 100 feet from the ground,

but the mixture of sand and oil lifted him 30 feet higher and when he fell it

was on the side of a soft sand pile, copiously tarred and ready for feathers.

Strange to say, he was not injured and got up and walked away.

Slides

like Panama

I stopped at some of the wells and watched

the drilling. The wells are never shot here with dynamite or other explosives,

as in United States. This is an account of the sand. The drilling is difficult

also on account of the different degrees of density of the various strata,

which causes the earth to slide in much the same way at it does at the Panama

canal. This forces the drill out of the perpendicular and often to such an

extent that a second hole is put down or the bent drill is cut through and the

hole extended. The soft earth formations add to the difficulty of carrying the

casings, and in a deep well the pipe sunk down at the top may be 25 inches in

diameter. After some distance a smaller casing is run down from the top and the

drill continued, growing smaller and smaller until the last casing which

strickes the oil is perhaps so small that a cat could nit run through it

without striking off electrical sparks with its fur.

I asked as to the cost of drilling and found

that the average expense of the well is 50,000 or 60,000 dollars, whereas 15 years ago oil was usually struck at a cost of about 15,000 dollars. Thirty years

ago, I am told, the cost of drilling a well at Lima, Ohio, was about 1,000 dollars.

Salt

Bed of Moreni

The queer feature of the Moreni field, the

producing area of which is only about 400 acres, is a huge wedge of salt, a

mile or so wide at the point and broadening out as it extends from the hills

down to the plains. The salt goes down no one knows how far. They have drilled

into it more than a half mile from the surface and have not found the end. The

wedge runs east and west, with the oil on both sides of it, and strange to say,

the oils are of different character. Those on the northern side of the wedge

have a paraffin base and those on southern side have an asphalt base. Standing

on the apex I could see the great derricks forming long lines on both sides of

the wedge. They were all black and somber, made so by the black sand and black

oil spray. This somberness is one of the features of these Romanian oil fields.

The pitchy fluid paints everything the color of jet. The buidings are black,

the machinery is black and even the ground is of a rich dark hue. In walking I

had to look out for my steps for fear I might sink to my shoe tops in one of

the oil swamps which are to be found here and there. I had to be especially

careful also, as I had an appoiment to lunch with the queen the following day

and had no other shoes with me but those on my feet.

What

a Geologist Said

A common expression in gold mining is that

the gold is where you find it. It is much the same with oil. Petroleum has been

mined commercially two years before Drake well was put down in the United

States. For a long time the wells were dug by hand and large basins about 15

feet square and 50 feet deep were made to hold the oil. At first the drillers

were not able to go below 150 feet, and they dropped snow in the well to purify

it. At least they claimed this purified it. Later wells were made by hand 600

and 800 feet deep and the oil sands were washed in large wooden vessels half

filled with water. The water forced the oil out of the sand and it floated on

the surface. Later still the oil was hauled out those dug wells in wooden

barrels up by means of a windlass, and sometimes ox-skins were used the same way,

just as they raise water in northern India today for irrigation.

After the foreing drillers came in

prospecting went on everywhere and new fields were discovered. Among those

tested was this Moreni field, against the advice of Geological Institute of

Romania. The Moreni field is now producing more than half the output and it yeld this year something

like 4,000,000 barrels.

Opportunities

for Foreigners

There are but few opportunities for wildcat

oil men in Romania. American prospectors come in, look over the ground, and go

away in disgust. One reason is the difficulties of drilling and another the

expense and last, but by no means least, is the strangle-hold which the government

has on industry. Acording to the laws enacted before and since the warm all the

oil taken out of the ground must be refined in Romania, and no crude oil, fuel

oil, or naphtha may be exported. Two-thirds of every oil product must be sold

in Romania at prices fixed by the government. This makes it possible to export

only one-third of the product. The gasoline, kerosene and other oils made in

the refineries have to be sold at miserable prices. For a long time the foreign

companies were delivering gasoline at four and five cents a gallon, when it was

selling at home for 27 and 30 cents. It is now selling here at eight or nine

cents a gallon, although the export price is 19 or 20 cents. The average price

of a tank car from the oil refineries is now 110 dollars in Romania, whereas the crude oil itself

at home is worth 132.5 dollars.

I understand also that preference is sometimes given to the Romanians as to oil

concessions, so on the whole I would not advise Americans to come here to make

oil investments.

In closing this letter I want to say a word

or so about the Standard Oil company here in Romania. Its investments amount to

upwords of 20,000,000 dollars.

It was one of the first foreign companies to aid in establishing the industry

and today it does a business larger than any other company with the exception,

perhaps, of the Royal Dutch Shell.

I have gone over its works and they are

wonders of efficiency and modern invention in a land where most of the methods

are crude to extreme. It has a high class force of men, and the American colony

which lives here at Ploiesti is a refreshing oasis in this great desert of East

Europe. On the outskirts of the town the company has some thousands of acres,

and here it has built up a settlement which might be transplanted bodily to the

best suburbs of any American city and not be out of place. Beautiful brick

houses of two stories each facing large, well kept lawns, decorated with trees

and flowers, run for perhaps a mile on each side of a wide macadamized roadway

not far from the refineries. The settlement has a good school and clubhouse. It

has tennis courts, ball grounds, and its swimming pool of the purest spring

water would cover a good-sized city lot. Every family has its own house, and

the homes are well furnished, having hot and cold water and being lighted by

electricity. The home life of the people is delightful and I am told that none

of them is anxious to leave."

BL FRANK G. CARPENTER

Carpenter’s World Travels, Copyright 1924.

Toledo Blade-Mar 27, 1924